- First Description

- Who gets Rheumatoid Vasculitis (the “typical” patients)?

- Classic symptoms of Rheumatoid Vasculitis

- What causes Rheumatoid Vasculitis?

- How is Rheumatoid Vasculitis diagnosed?

- Treatment and Course of Rheumatoid Vasculitis

- What’s new in Rheumatoid Vasculitis?

First Description

Rheumatoid Vasculitis (RV) is an unusual complication of longstanding, severe rheumatoid arthritis. The active vasculitis associated with rheumatoid disease occurs in about 1% of this patient population.

RV is a manifestation of “extra-articular” (beyond the joint)rheumatoid arthritis and involves the small and medium-sized arteries in the body. In many of its disease features, RV resembles polyarteritis nodosa.

Other common extra-articular manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis, such as inflammation in the sac surrounding the heart (pericarditis), inflammation in the lining of the lungs (pleuritis), and interstitial lung disease (resulting in fibrosis or scarring of the lungs).

Who gets Rheumatoid Vasculitis? A typical patient

RV can affect a person from any ethnic background, either gender, and from any age group. However, more often than not, the typical patient has long-standing rheumatoid arthritis with severe joint deformities from the underlying arthritis. Although the arthritis has usually led to significant joint damage, at the onset of RV the joint disease is paradoxically quiet.

Figure: Patient with joint damage from rheumatoid arthritis. Note the bulbous swelling of some knuckles and lateral (ulnar) deviation of the fingers.

Classic symptoms of Rheumatoid Vasculitis

RV has many potential signs and symptoms. The manifestations of RV can involve many of the body’s different organ systems, including but not limited to the skin, peripheral nervous system (nerves to the hands and feet) , arteries of the fingers and toes causing digital ischemia, and eyes with scleritis. Scleritis (inflammation of the white part of the eye) commonly occurs in the setting of RV. This ocular complication requires urgent treatment with immunosuppressive medications.

Figure: Digital ischemia – this image shows a blood flow deficiency in the tip of the finger caused by an obstruction of the digital artery.

Figure: Scleritis – Inflammation of the sclera (the white of the eye) causing redness, light sensitivity and pain.

In addition, generalized symptoms such as fever and weight loss are common.

As is true with other forms of vasculitis that involve the skin, cutaneous lesions can erupt on various areas of the body in RV, with a predilection for the lower extremities. Typical findings include ulcers concentrated near the ankles.

Figure: Cutaneous ulcer – an open skin sore caused by an obstruction of the small blood vessels in the superficial ulcers or obstruction of medium vessels in a deeper ulcer.

Small nail fold infarcts (small spots around fingernail) can

occur in rheumatoid arthritis

but these do not necessarily signify the presence of systemic vasculitis and do not necessitate a change in rheumatoid arthritis treatment.

Nerve damage can cause foot or wrist drop, known in medical terminology as “mononeuritis multiplex”. The images below show a patient with a right wrist drop and a patient with right foot drop. This condition, which may be significantly disabling, is often preceded by a change in sensation in the same area (numbness, tingling, burning, or pain). These abnormal sensations can progress to muscle weakness, focal paralysis, and eventually to muscle wasting. Recovery from this condition, caused by nerve infarction, can take months. In some cases, recoveries from mononeuritis multiplex are incomplete.

Figures of drop wrist and drop foot (courtesy of the University of North Carolina)

(Video of drop foot viewable on our Microscopic Polyangiitis page under classic symptoms.)

Laboratory Tests

Most laboratory findings in RV – for example, elevations in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein – are non-specific, and reflect the presence of a generalized inflammatory state. Hypocomplementemia, anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA), and atypical anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA) are common. Rheumatoid factor levels are usually extremely elevated. However, there is no definitive laboratory test for RV short of a tissue biopsy. The diagnosis must usually be made using a combination of history, physical examination, pertinent laboratory investigations, specialized testing (e.g., nerve conduction studies), and sometimes a tissue biopsy.

Because the treatment implications for RV are major, any diagnostic uncertainty must be met with definitive approaches to establishing the diagnosis. This usually involves biopsy of an involved organ. Deep skin biopsies (full-thickness biopsies that include some subcutaneous fat) taken from the edge of ulcers are very useful in detecting medium-vessel vasculitis. Nerve conduction studies help identify involved nerves for biopsy. Muscle biopsies (e.g., of the gastrocnemius muscle) should be performed at the same time as nerve biopsies, to increase the chance of finding changes characteristic of vasculitis. Imaging studies have no consistent role in the evaluation of RV, although sometimes angiography of the gastrointestinal tract is useful.

What Causes Rheumatoid Vasculitis?

The cause of RV is unknown, but given the prominence of immune components and the pathologic changes in involved blood vessels, an auto-immune process is suggested.

How is Rheumatoid Vasculitis diagnosed?

Most laboratory findings in RV – for example, elevations in the erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein are non-specific, and reflect the presence of a generalized inflammatory state. Hypocomplementemia, anti-nuclear antibodies (ANAs), and atypical anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (atypical ANCAs) are common. Rheumatoid factor levels are extremely elevated, as a rule. However, there is no definitive laboratory test for RV short of a tissue biopsy. The diagnosis must usually be made by the combination of history, physical examination, pertinent lab work, other specialized testing (e.g., nerve conduction studies), and sometimes even a tissue biopsy is required.

The diagnosis of RV should be considered in any rheumatoid arthritis patient who develops new constitutional symptoms, skin ulcerations, decreased blood flow to the fingers or toes, symptoms of a sensory or motor nerve dysfunction (numbness, tingling, focal weakness); or any inflammation of the lining around the heart or lungs (pericarditis or pleurisy/pleuritis).

Patients with a history of joint-destructive rheumatoid arthritis are at an increased risk for infection. Therefore, when a rheumatoid arthritis patient presents with a new onset of non-specific systemic complaints an infection must first be eliminated. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis typically have immune systems that are disordered from previous immunosuppression and underlying disease (e.g., joint damage). This patient population, therefore, is at higher risk of infection.

The differential diagnosis of RV includes:

- Cholesterol embolization syndromes, in which a piece of cholesterol breaks off of a plaque, may cause digital ischemia (blood flow obstruction to a finger or toe), and a host of other symptoms that mimic vasculitis.

- Diabetes mellitus is another major cause of mononeuritis multiplex, but multiple mononeuropathies occurring over a short period of time are unusual in diabetes.

- Many clinical features of RV mimic those of polyarteritis nodosa, cryoglobulinemia, and other forms of necrotizing vasculitis. Therefore they too should be considered in this setting.

Because the treatment implications for RV are major, any diagnostic uncertainty must be met with a definitive approach to establishing the diagnosis. As alluded to earlier, this usually involves the biopsy of an involved organ. Deep skin biopsies (full-thickness biopsies that include some subcutaneous fat) taken from the edge of ulcers are very useful in detecting medium-vessel vasculitis. Nerve conduction studies help identify involved nerves for biopsy. Muscle biopsies (e.g., of the gastrocnemius muscle) should be performed at the same time as nerve biopsies, to increase the chance of finding changes characteristic of vasculitis. Imaging studies have no consistent role in the evaluation of RV, although sometimes angiography of the gastrointestinal tract is useful.

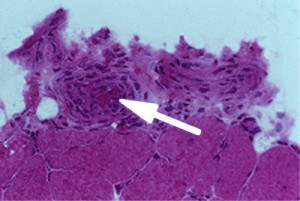

Normally, the cells of the blood vessel wall would be fewer in number (less thick) and the lumen (larger red area) would be larger. The arrow points (Figure 6, left) to an inflamed blood vessel found on a muscle biopsy. The globular pink areas are muscle fibers.

Treatment and Course of Rheumatoid Vasculitis

Therapy should reflect the severity of organ involvement. Prednisone or other steroid therapies are often the first line of treatment. Optimizing treatment of the underlying rheumatoid arthritis is also essential, therefore medications such as methotrexate or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors may be employed. In the setting of impending damage to major organs such as the eyes, a peripheral nerve, the gastrointestinal tract, or of a severe skin ulceration, cyclophosphamide is usually warranted.

What’s New in Rheumatoid Vasculitis?

Compared to other forms of vasculitis, there has been relatively little research in recent years on the specific entity of RV. The lack of similarity in available reports on RV and discrepancies in case definitions have created challenge to building standard approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of this condition. There is some evidence that the incidence of RV has decreased over the past several decades, perhaps because of better treatment of the underlying rheumatoid arthritis.