- First Description

- Who gets Microscopic Polyangiitis (the “typical” patients)?

- Classic symptoms of Microscopic Polyangiitis

- Forms of vasculitis similar to Microscopic Polyangiitis

- What causes Microscopic Polyangiitis?

- How is Microscopic Polyangiitis diagnosed?

- Treatment and Course of Microscopic Polyangiitis

First Description

The first description of a patient with the illness now known as microscopic polyangiitis (MPA) appeared in the European literature in the 1920s. The concept of this disease as a condition that is separate from polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and other forms of vasculitis did not begin to take root in medical thinking, however, until the late 1940s. Even today, some confusing terms for MPA (e.g., “microscopic poly arteritis nodosa ” rather than “microscopic poly angiitis ”) persist in the medical literature. Confusion regarding the proper nomenclature of this disease led to references to “microscopic polyarteritis nodosa” and “hypersensitivity vasculitis” for many years. In 1994, The Chapel Hill Consensus Conference recognized MPA as its own entity, distinguishing it in a classification scheme clearly from PAN, granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA, formerly Wegener’s), cutaneous leukocytoclastic angiitis (CLA), and other diseases with which MPA has been confused with through the years.

Much of the explanation for the difficulty in separating MPA from other forms of vasculitis has stemmed from the numerous areas of overlap of MPA with other diseases. MPA, PAN, GPA, and CLA and other disorders all share a variety of features but possess sufficient differences as to justify separate classifications.

Who gets Microscopic Polyangiitis? A typical patient

MPA can affect individuals from all ethnic backgrounds and any age group. In the United States, the typical MPA patient is a middle-aged white male or female, but many exceptions to this exist. The disease may occur in people of all ages, both genders, and all ethnic backgrounds.

Classic symptoms of Microscopic Polyangiitis

Many signs and symptoms are associated with MPA. This disease can affect many of the body’s organ systems including (but not limited to) the kidneys, nervous system (particularly the peripheral nerves, as opposed to the brain or spinal cord), skin, and lungs. In addition, generalized symptoms such as fever and weight loss are very common.

The FIVE most common clinical manifestations of MPA are:

- Kidney inflammation (~ 80% of patients).

- Weight loss (> 70%).

- Skin lesions (> 60%).

- Nerve damage (60%).

- Fevers (55%).

Kidney Inflammation

Inflammation in the kidneys, known as glomerulonephritis, causes blood and protein loss through the urine. This process can occur either slowly or very rapidly in the course of the disease. Patients with kidney inflammation may experience fatigue, shortness of breath, and swelling of the legs.

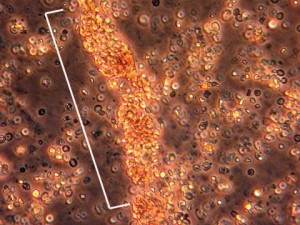

The image below is from a urinalysis of a patient with kidney inflammation. When MPA is active, red blood cells will form a clump or “cast” (bracketed in white) within the tubules of inflamed kidneys. These “casts” pass through the renal system and may be viewed under the microscope in a patient’s urine.

Constitutional Symptoms

Weight loss, fevers, fatigue, and malaise are part of a collection of complaints regarded as “constitutional” symptoms. Constitutional complaints are a common finding in patients with MPA, because the disorder is a systemic disease confining itself generally not to one specific organ system but rather broadly affecting a patient’s “constitution”.

Skin lesions

Skin lesions in MPA, as in other forms of vasculitis that involve the skin, can erupt on various areas of the body. The lesions tend to favor the “dependent” areas of the body, specifically the feet, lower legs and, in bed-ridden patients, the buttocks. The skin findings of cutaneous MPA include purplish bumps and spots pictured below (palpable purpura).

These areas range in size from several millimeters in diameter to coalescent lesions that are even larger. Skin findings in MPA may also include small flesh-colored bumps (papules); small-to-medium sized blisters (vesiculobullous lesions); or as small areas of bleeding under the nails that look like splinters (pictured below), hence the name splinter hemorrhages.

Peripheral nervous system

Damage to peripheral nerves (i.e., nerves to the hands and feet, arms and legs) results from inflammation of the blood vessels that supply the nerves with nutrients. Inflammation in these blood vessels deprives the nerves of their nutrients, leading to nerve infarction (tissue death). Multiple nerve involvement that is characteristic of vasculitis is known as “mononeuritis multiplex”. This condition is frequently associated with wrist or foot drop: the inability to extend the hand “backwards” at the wrist or to flex the foot upward toward the head at the ankle joint. If the condition is caused by nerve deterioration associated with vasculitis, unfortunately, surgery is not a treatment option due to the nerve infarcton (tissue death).

Neurologic symptoms resulting from peripheral nerve damage may also include numbness or tingling in the arm, hand, leg, or foot. Over time, muscle wasting (pictured below) that is secondary to the nerve damage may result from damage caused by vasculitis.

Pictured:

The hand on the left (the patient’s right hand) is normal, displaying normal muscle bulk of the areas between the fingers. In contrast, the hand on the right (the patient’s left) shows wasting of the muscle in the web space between the thumb and first finger, leading to a hollowed-out, bowl-like appearance of that area. The consequence of this muscle wasting is that the patient is unable to grasp objects between his thumb and fingers (i.e., has a weak pinch) and his hand grip is weak.

Lungs

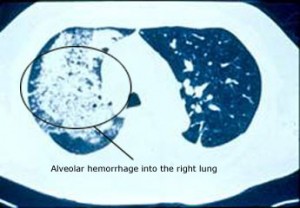

Lung involvement can be a dramatic and life-threatening manifestation of MPA. When lung disease takes the form alveolar hemorrhage – bleeding from the small capillaries that are in contact with the lungs’ microscopic air sacs – the condition may quickly pose a threat to the patient’s respiratory status (and therefore to the patient’s life). Alveolar hemorrhage (pictured below), which is frequently heralded by the coughing up of blood, occurs in approximately 12% of patients with MPA .

Another common lung manifestation of MPA is the development of non-specific inflammatory infiltrates, identifiable on chext x-rays or computed tomography (CT scans) of the lung.

Eyes, Muscles, and Joints

Organs that also merit mention in discussions of MPA include the eyes, muscles, and joints. Intermittent irritation of the eye (resembling “pinkeye”) that is caused by either conjunctivitis or episcleritis may be an early disease manifestation or a sign of a disease flare. Occasionally other types of inflammation (e.g., uveitis) are also observed in MPA. Muscle or joint pains (known to clinicians as “myalgias” or “arthralgias”, respectively) are common complaints in MPA, generally accompanying the types of constitutional symptoms mentioned above. Arthritis (inflammation of the joints accompanied by swelling) can also be observed in MPA. Joint complaints in MPA and related forms of vasculitis tend to migrate from one joint to another – one day involving the left ankle, the next day the right wrist, the third day a shoulder, for example.

Forms of vasculitis similar to Microscopic Polyangiitis

The similarities and differences between MPA, GPA, and PAN are highlighted in the table below.

| MPA | GPA | PAN | |

| BLOOD VESSEL SIZE | Small to Medium | Small to Medium | Medium |

| BLOOD VESSEL TYPE | Arterioles to venules, And sometimes Arteries and veins | Arterioles to venules, And sometimes Arteries and veins | Muscular Arteries |

| GRANULOMATOUS INFLAMMATION | NO | YES | NO |

| LUNG SYMPTOMS | YES1 | YES1 | NO |

| GLOMERULONEPHRITIS | YES | YES | NO |

| RENAL HYPERTENSION | NO | NO | YES |

| MONONEURITIS MULTIPLEX | COMMON | OCCASIONAL | COMMON |

| SKIN LESIONS | YES2 | YES2 | YES2 |

| GI SYMPTOMS | NO | NO | YES3 |

| EYE SYMPTOMS | YES4 | YES4 | NO |

| ANCA-POSITIVITY | 75% | 65-90% | NO |

| CONSTITUTIONALSYMPTOMS | YES5 | YES5 | YES5 |

| NECROTIZING TISSUE | YES | YES | YES |

| MICROANEURYSMS | RARELY | RARELY | TYPICAL |

1 Pulmonary capillaritis in MPA and nodules or cavitary lesions in WG

2MPA can have small blood vessel skin lesions as mentioned above, similar to GPA or medium blood vessel lesions similar to PAN (livedo reticularis, nodules, ulcers, and digital gangrene)

3Stomach pain after meals

4MPA eye complications are typically milder than those of GPA, but serious

ocular problems including necrotizing scleritis can occur

5Constitutional symptoms include weight loss, fevers, joint and muscle aches, and malaise.

What Causes Microscopic Polyangiitis?

The cause of MPA is not known. However, enough is known about a few types of vasculitides that allow us to describe in general terms how MPA affects the body. MPA is clearly a disorder that is mediated by the immune system; the precise events leading to the immune system dysfunction (hyperactivity), however, remain unclear. Many elements of the immune system are involved in this process: neutrophils, macrophages, T and B lymphocytes, antibodies, and many, many others.

Because MPA is often associated with anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), antibodies directed against certain constituents of white blood cells (WBCs), the disease is often termed an “ANCA-associated vasculitis”, or AAV. ANCA, discovered in 1982, act against certain specific (and naturally occurring) enzymes in the body residing within the neutrophils and the macrophages, all of which are members of the WBC family. The result of the interactions of ANCA with their target proteins is an increase in the destruction of WBCs at the sites of disease and the release of white blood cell enzymes within blood vessel walls, causing the damage to blood vessels. In MPA, the ANCA are directed generally against to specific proteins: myeloperoxidase (MPO) and proteinase 3 (PR3).

How is Microscopic Polyangiitis diagnosed?

Blood is taken to detect any ANCA levels, if MPA is suspected. In addition, an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR or “sed rate”) and C-reactive protein (CRP) are usually ordered. Both of these tests are elevated in many different types of inflammation and are not specific to MPA or any particular disease. The ESR and CRP, known as “acute phase reactants”, are often sensitive indicators of the presence of active disease. In and of themselves, however, elevations in acute phase reactants are not sufficient to justify additional treatment.

A carefully analyzed urine specimen should be obtained at the initial visit (and every follow-up visit!) to maintain vigilance for either the development or the progression of kidney involvement.

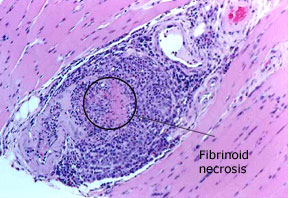

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest may also be performed to detect the presence of lung involvement. A tissue biopsy may be needed to make the diagnosis of MPA, and is taken from an organ that seems to be involved at the time. Sometimes an electromyography/nerve conduction (EMG/NCV) study may need to be done to identify a site for biopsy or to detect findings consistent with a mononeuritis multiplex (see classic symptoms section above). Tissues that might be biopsied are kidney, skin, nerve, muscle, and lung.

Pictured: a biopsy of the gastrocnemius muscle, performed in a 69 year–old man with microscopic polyangiitis. A blood vessel within the muscle shows an intense inflammatory infiltrate with destruction of the blood vessel wall, confirming the diagnosis of vasculitis.

Treatment and Course of Microscopic Polyangiitis

A steroid (usually prednisone) in combination with a cyclophosphamide (CYC) or rituximab is typically the first combination of medications to be prescribed. After control of the disease – usually around 4 – 6 months of treatment maintenance therapy will be used to keep the disease in remission. This will vary between patients. Prednisone may be discontinued after approximately 6 months.