The name literally means “cold antibody in the blood”, which refers to the chemical properties of the antibodies that cause this disease: cryoglobulins are antibodies that precipitate under cold conditions. Drug use is a prime risk factor for cryoglobulinemia because more than 90% of cases of cryoglobulinemic vasculitis are associated with hepatitis C infections. Hepatitis C is acquired by injection drug use (needle–sharing), tainted blood products, and (probably rarely), sexual transmission. Treatment of the underlying hepatitis may be an effective therapy for this type of vasculitis.

Pictured below is the hand from the same patient at different times. The image on the left is normal and the one on the right shows the patient in the midst of a flare of cryoglobuinemic vasculitis.

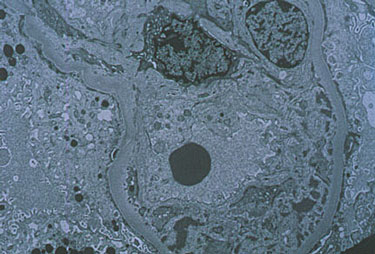

Pictured below is an electron micrograph of a kidney biopsy specimen from a patient with cryoglobulinemia.

In medical terms, by David Hellmann, M.D.

A discussion of Cryoglobulinemia written in medical terms by David Hellmann, M.D. (F.A.C.P.), Co-Director of the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center, for the Rheumatology Section of the Medical Knowledge Self-Assessment Program published and copyrighted by the American College of Physicians (Edition 11, 1998). The American College of Physicians has given us permission to make this information available to patients contacting our Website.

Cryoglobulins are immunoglobulins that precipitate in the cold and disolve on rewarming. Three types of cryoglobulins are distinguished based on whether the cryoglboulin is monoclonal and has rheumatoid factor activity. Knowing the type usually allows the physician to predict the clinical features; alternatively knowing the clinical features allows one to deduce the type of cryoglobulin. Type I is a monoclonal antibody that does not have rheumatoid factor activity. Most commonly, type I is associated with lymphoma, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, and multiple myeloma. Because type I cryoglobulins do not easily activate complement, patients with type I are asymptomatic until the level of cryoglobulinemia is sufficiently high to cause hyperviscosity syndrome. Both types II and III are rheumatoid factors — antibodies that bind to the Fc fragment of IgG. Therefore, both types are called mixed cryoglobulins. In type II, the rheumatoid factor is monoclonal, whereas in type III it is polyclonal. Type II is associated with lymphoproliferative diseases, and both types can occur in patients with rheumatic diseases and chronic infections. Cryoglobulinemia is said to be essential when there is no identifiable underlying disease. Type II and III cryoglobulinemia frequently presents as vasculitis, most commonly with recurrentlower extremity purpura, glomerulonephritis, and peripheral neuropathy.

It is now evident that most patients diagnosed with type II or type III mixed essential cryoglobulinemia have the disease as an immune response to chronic hepatitis C infection. The role of hepatitis C virus is suggested by finding that the cryoglobulins in these patients are enriched with anti–hepatitis C antibody and hepatitis C RNA. Moreover, antviral therapy can remit the disease in some patients.

Treatment depends on the type of cryoglobulin, underlying disease, and severity of symptoms. Cryoglobulinemia with severe hyperviscosity syndrome requires plasmapheresis and chemotherapy of the underlying malignancy. Some patients with cryoglobulinemia suffer from mild, recurrent crops of lower extremity purpura that require no specific therapy. More extensive vasculitis associated with autoimmune diseases or essential cryoglobulinemia may respond to prednisone, cyclophosphamide, or both. The most effective treatment for cryoglobulinemia associated with hepatitis C has not yet been determined. Brief use of prednisone followed by 6 months of interferon alfa has produced clinical and liver function test improvement, but relapse of liver disease and vasculitis often occurs when interferon alfa is stopped.