- First Description

- Who gets Behcet’s Disease (the “typical” patients)?

- Classic symptoms of Behcet’s Disease

- What causes Behcet’s Disease?

- How is Behcet’s Disease diagnosed?

- Treatment and Course of Behcet’s Disease

- What’s new in Behcet’s Disease?

First Description

In the 1930’s, a Turkish dermatologist, Hulusi Behcet, noted the triad of aphthous oral ulcers, genital lesions, and recurrent eye inflammation, and became the first physician to describe the disease in modern times. Another name for Behcet’s Disease is Behcet’s syndrome.

Who gets Behcet’s Disease (the “typical” patient)?

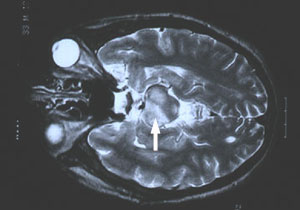

Behcet’s disease is most common along the “Old Silk Route,” which spans the region from Japan and China in the Far East to the Mediterranean Sea, including countries such as Turkey and Iran. Although the disease is rare in the United States, sporadic cases do occur in patients who would not appear to be at risk because of their ethnic backgrounds (e.g., in Caucasians or African–Americans). The disease is not rare in regions along the Old Silk Route, but the disease’s epidemiology is not well understood. In Japan, Behcet’s disease ranks as a leading cause of blindness. Below is a magnetic resonance image (MRI) study of a Behcet’s patient demonstrating central nervous system involvement (white matter changes in the pons).

Classic symptoms and signs of Behcet’s Disease

Behcet’s disease is virtually unparalleled among the vasculitides in its ability to involve blood vessels of nearly all sizes and types, ranging from small arteries to large ones, and involving veins too. Because of the diversity of blood vessels it affects, manifestations of Behcet’s may occur at many sites throughout the body. However, the disease has a predilection for certain organs and tissues; these are described below.

Eye

- Behcet’s may cause either anterior uveitis (inflammation in the front of the eye) or posterior uveitis (inflammation in the back of the eye), and sometimes causes both at the same time.

- Anterior uveitis results in pain, blurry vision, light sensitivity, tearing, or redness of the eye.

- Posterior uveitis may be more dangerous and vision–threatening because it often causes fewer symptoms while damaging a crucial part of the eye — the retina.

Mouth

- Painful sores in the mouth called “aphthous ulcers”(pictured below). These are very similar in appearance to ulcers that frequently occur in the general population, usually as a result of minor trauma. In Behcet’s, however, the lesions are more numerous, more frequent, and often larger and more painful. Aphthous ulcers can be found on the lips, tongue, and inside of the cheek. Aphthous ulcers may occur singly or in clusters, but occur in virtually all patients with Behcet’s.

Skin

- Pustular skin lesions that resemble acne, but can occur nearly anywhere on the body. This rash is sometimes called “folliculitis”.

- Skin lesions called erythema nodosum: red, tender nodules that usually occur on the legs and ankles but also appear sometimes on the face, neck, or arms. Unlike erythema nodosum associated with other diseases (which heal without scars), the lesions of Behcet’s disease frequently ulcerate.

Lungs

- Aneurysms (outpouchings of blood vessel walls, caused by inflammation) of arteries in the lung, rupture of which may lead to massive lung hemorrhage.

Joints

- Arthritis or “arthralgias” (pain in the joints not accompanied by joint swelling).

Brain

- Central nervous system involvement is one of the most dangerous manifestations of Behcet’s. The disease tends to involve the “white matter” portion of the brain and brainstem, and may lead to headaches, confusion, strokes, personality changes, and (rarely) dementia. Behcet’s may also involve the protective layers around the brain (the meninges), leading to meningitis. Because the meningitis of Behcet’s disease is not associated with any known infection, it is often referred to as “aseptic” meningitis.

Genitals

- Male — painful genital lesions that form on the scrotum, similar to oral lesions, but deeper.

- Female — painful genital ulcers that develop on the vulva.

Gastrointestinal

- Ulcerations may occur anywhere in the gastrointestinal tract from the mouth to the anus. The terminal ileum and cecum are common sites. Involvement of the GI tract by Behcet’s may be difficult to distinguish from inflammatory bowel disease (such as Crohn’s disease).

Blood Vessels

- Clots can occur in veins in any site, most often including veins in the lower extremity (superficial or deep venous thrombosis).

- Inflammation in arteries can occur as well, such as the pulmonary or abdominal arteries, sometimes causing obstruction of the vessel (thrombosis).

What causes Behcet’s Disease?

Behcet’s is one of the few forms of vasculitis in which there is a known genetic predisposition. The presence of the gene HLA–B51 is a risk factor for this disease. However, it must be emphasized that presence of the gene in and of itself is not enough to cause Behcet’s: many people possess the gene, but relatively few develop Behcet’s. Despite the predisposition to Behcet’s conferred by HLA–B51, familial cases are not the rule, constituting only about 5% of cases. Thus, it is believed that other factors (perhaps more than one) play a role. Possibilities include infections and other environmental exposures.

How is Behcet’s Disease Diagnosed?

There is not one specific test to diagnose Behcet’s. Rather the diagnosis is based on the occurrence of symptoms and signs that are compatible with the disease. The presence of certain features that are particularly characteristic (e.g., oral or genital ulcerations), elimination of other possible causes of the patient’s symptoms, and if possible, proof of vasculitis by biopsy of an involved organ would together support a diagnosis of Behcet’s.

A positive pathergy test can be supportive of the diagnosis of Behcet’s but is not diagnostic by itself of the condition. A pathergy test is a simple test in which the forearm is pricked with a small, sterile needle. Occurrence of a small red bump or pustule at the site of needle insertion constitutes a positive test. Please note, that although a positive pathergy test is helpful in the diagnosis of Behcet’s, only a minority of Behcet’s patients demonstrate the pathergy phenomenon (i.e., have positive tests). Patients from the Mediterranean region are more likely to demonstrate pathergy. In addition, other conditions can occasionally result in positive pathergy tests, so the test is not 100% specific.

Pictured below is an example of the pathergy test; 1) taken at the time when the patient was “stuck” with the sterile needle; 2) shows the area immediately after the stick; 3) & 4) show the area one day and two days after the needle stick, respectively.

Treatment and Course of Behcet’s Disease

For disease that is confined to mucocutaneous regions (mouth, genitals, and skin), topical steroids and non–immunosuppressive medications such as colchicine or dapsone may be effective. Apremilast (Otezla) is now FDA-approved for treatment of oral ulcers in Behcet’s. Moderate doses of systemic corticosteroids are also frequently required for disease exacerbations. Some patients require chronic, low doses of prednisone or conventional immunosuppressives such as (azathioprine) to keep the disease under control.

In the event of serious end–organ involvement such as eye or central nervous system disease, both high doses of prednisone and some other form of immunosuppressive treatment are usually necessary. Immunosuppressive agents used in the treatment of Behcet’s include azathioprine, cyclosporine, cyclophosphamide, and TNF-alpha inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumuab). Cyclophosphamide is generally used in life-threatening disease, such as central nervous system involvement. Blood clots can be another manifestation of Behcet’s, and in some scenarios blood thinners may be used in treatment.