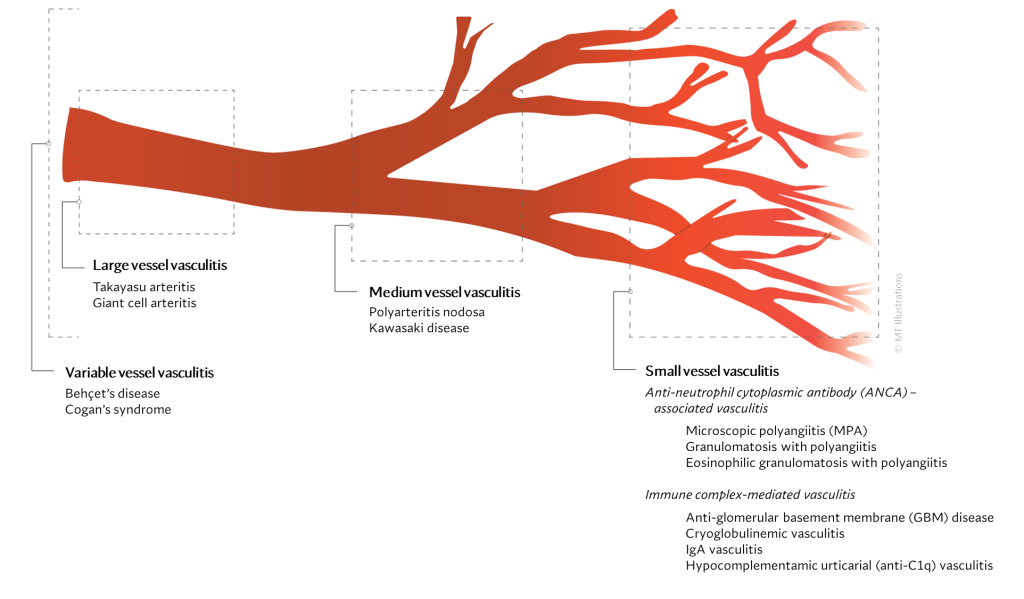

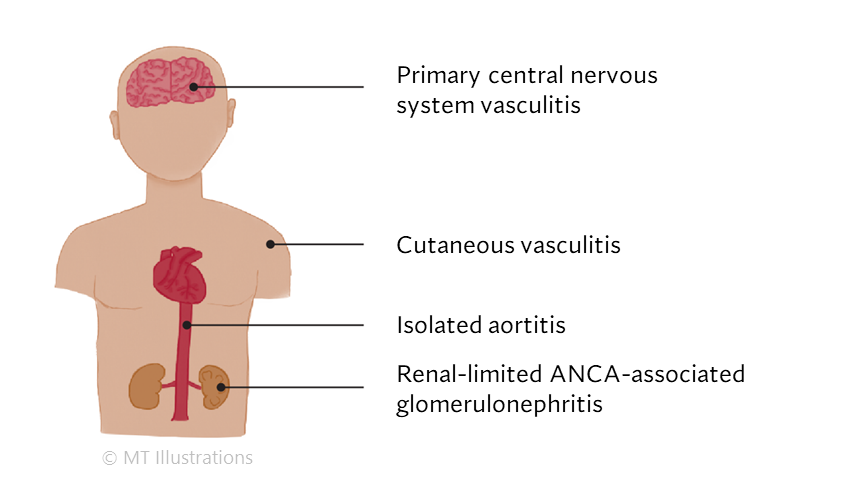

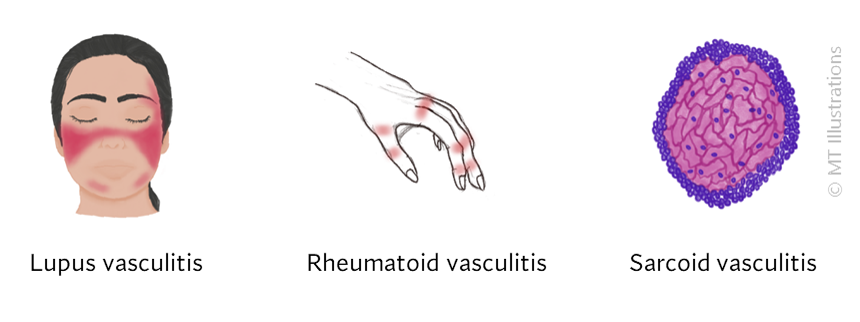

There are many different types of vasculitis, some with different causes than others.

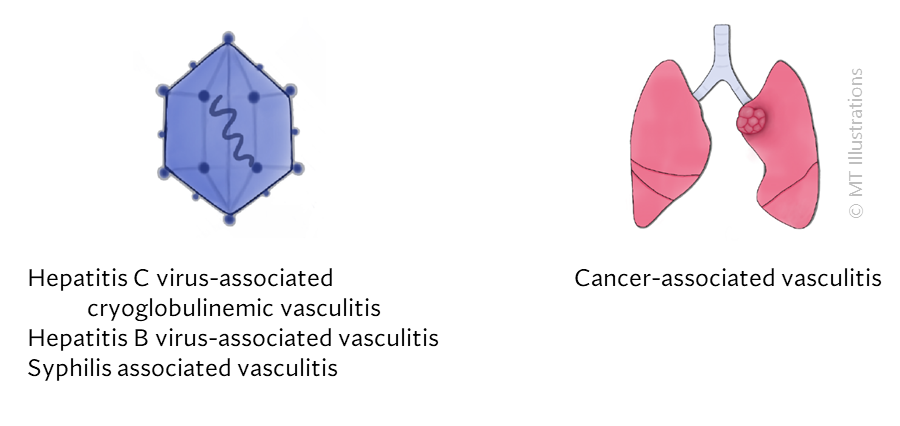

Certain forms of vasculitis that can be due to infection where the microbe directly invades the vessel wall. Syphilis is one example of vasculitis that can be caused by infection in the blood vessel. Treating the infection is the main goal in managing this sort of vasculitis, which is not an autoimmune disease, but rather an infection.

Other infections can provoke the immune system into causing damage in blood vessels. Here, the infection is the trigger, but the immune system is the cause of the vascular damage. Viral hepatitis (B and C) are examples of this sort: some patients with Hepatitis B may develop polyarteritis nodosa, while some patients with Hepatitis C may develop cryoglobulinemic vasculitis.

Other types of vasculitis may be due to an ‘allergic‘-type reaction to medications. For example, certain blood pressure medications (hydralazine) or thyroid medications (propylthiouracil) can trigger ANCA associated vasculitis in some patients. Cocaine is an illicit drug that is linked to vasculitis and vascular damage.

However, the causes of most vasculitides are currently unknown. While we can identify some risk factors (such as older age in giant cell arteritis), we do not know the specific causes of these diseases. These forms of vasculitis of unknown cause are considered autoimmune diseases.

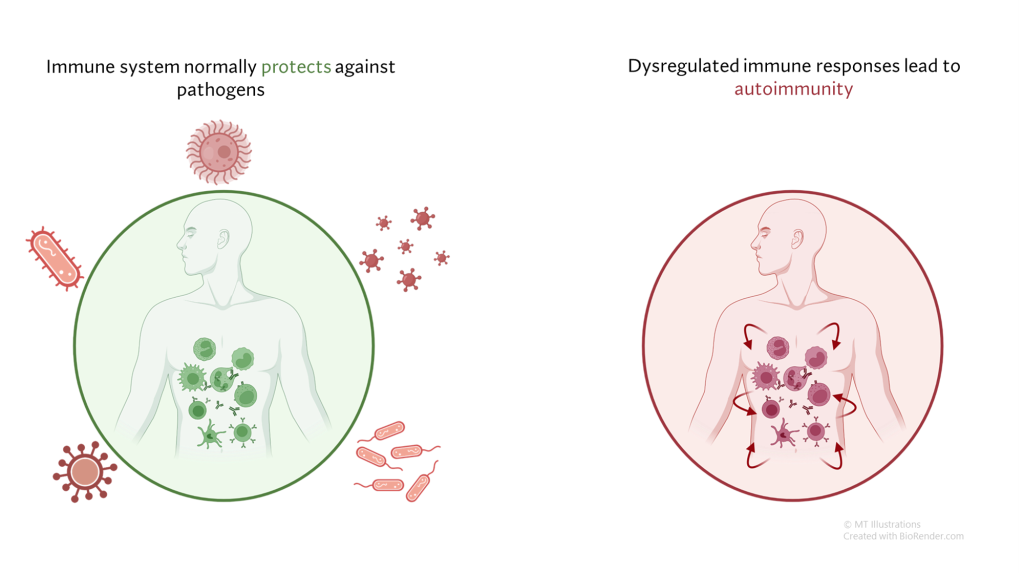

Under normal circumstances, our immune system serves to defend us from infection and other threats, such as cancers. In autoimmune diseases, the immune system generates a response not against a foreign threat, but against normal “self” tissues. This abnormal immune response against “self” tissues can result in a wide array of autoimmune diseases, including relatively common diseases (such as psoriasis or thyroid disease) as well as rare conditions (such as vasculitis).

In most cases, autoimmune diseases are believed to be due to an abnormal immune response that is generated in a susceptible person, and eventually leads to a cycle of ongoing inflammation in otherwise normal tissues where no infection or other identifiable threat is present. Some interaction between the immune system and the environment is thought necessary for this to occur, and a person’s genetic background likely places some individuals at higher risk than others.

A better understanding of the specific causes of these diseases would lead to improved means of diagnosing, treating, and even preventing these conditions. Uncovering the causes of vasculitis is a major goal of vasculitis research.

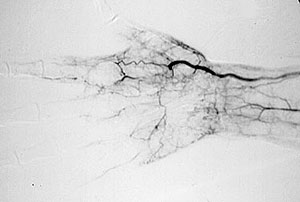

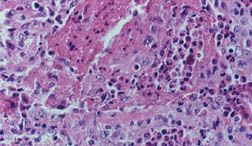

While we may not know the specific causes of the vasculitidies, we do have a basic understanding of the way that the immune system causes organ damage in these conditions. In all forms of vasculitis, activation of the immune system leads to the deposition of inflammatory cells and proteins in the walls of blood vessels. As this inflammation in blood vessels continues, the vessels become damaged and no longer serve their normal function of delivering blood to the organs that they supply. Consequently, the tissues downstream of these inflamed vessels are starved of oxygen and nutrients needed for normal function. At a basic level, this is a process similar to what occurs in a heart attack or a stroke – but instead of the cholesterol plaque that blocks a coronary artery in a heart attack, the immune system is responsible for blockage of blood vessels in vasculitis.

All information contained within the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center website is intended for educational purposes only. Visitors are encouraged to consult other sources and confirm the information contained within this site. Consumers should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they may have read on this website.