- How do we Diagnose Vasculitis?

- Skin Biopsy

- Kidney Biopsy

- Sural Nerve Biopsy

- Temporal Artery Biopsy

- Lung Biopsy

- Brain Biopsy

- Abdominal Angiogram

- Central Nervous System Angiogram

- Other Useful Tests

How do we diagnose Vasculitis?

Patients with vasculitis learn that making the diagnosis is sometimes quite difficult. Many endure numerous doctors’ visits, tests, and hospitalizations before the pieces of the puzzle are assembled. The diagnosis of vasculitis usually requires a biopsy of an involved organ (skin, kidney, lung, nerve, temporal artery). This allows us to ‘see’ the vasculitis by looking under a microscope to see the inflammatory immune cells in the wall of the blood vessel. Although, making a diagnosis of vasculitis can be quite involved, this is very important for two main reasons:

# ONE: Vasculitis has many MIMICKERS (other diseases that have similar features but require different treatments). It is important to rule out other causes of vascular inflammation, other than a primary autoimmune condition as the management could be different.

# TWO: The treatments for vasculitis itself involve substantial risk. No physician should prescribe such treatment without making every effort to secure a firm diagnosis.

Blood tests, X–rays, and other studies may suggest the diagnosis of vasculitis, but often the only way to clinch the diagnosis is to biopsy involved tissue, examine the tissue under the microscope in consultation with a pathologist (ideally one experienced at examining biopsies in vasculitis), and find the pathologic hallmarks of the disease.

If a patient’s symptoms, physical examination, and diagnostic testing suggest involvement of a particular organ, one of the procedures below may be used to confirm (or exclude) the diagnosis of vasculitis:

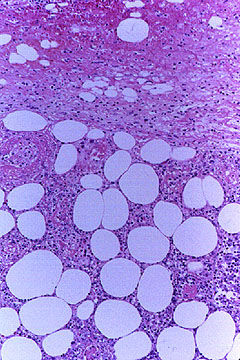

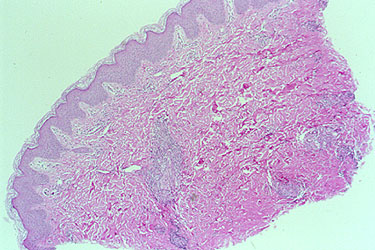

1. Skin Biopsy: One of the least invasive ways of making the diagnosis. A minor procedure performed under local anesthesia. The wound is closed with 1–2 stitches that are removed 7–10 days later.

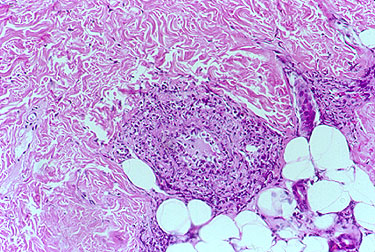

An abnormal skin biopsy showing leukocytoclastic vasculitis. The white oval shapes are subcutaneous fat cells beneath the dermis.

An example of an inadequate skin biopsy.

The correct diagnosis of PAN (polyarteritis nodosa) was not confirmed by this biopsy because the biopsy was not deep enough. The biopsy specimen contains only the epidermis and superficial dermis. PAN classically affects medium–sized arteries located in the deep dermis.

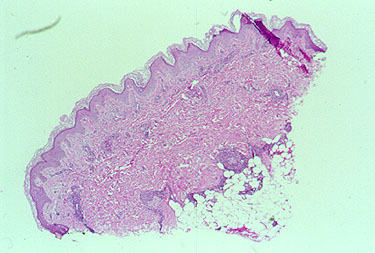

In contrast to the biopsy above, the skin biopsy below was deep enough to include the deep dermis as well as some subcutaneous fat.

The white, oval–shaped areas are fat lobules. Just superficial to the subcutaneous fat, within the deep dermis, an inflamed medium–sized vessel is evident.

A closer view of the vessel is provided in the next figure which provides a high power view of the vasculitic artery lying at the junction of the dermis and subcutaneous fat.

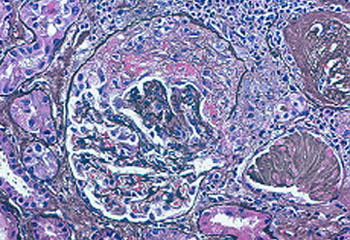

2. Kidney Biopsy: A kidney biopsy will be performed if there is evidence of kidney involvement by vasculitis (red blood cells or protein in the urine, for example). This procedure is done under local anesthesia while the kidney is visualized by ultrasound. Because of the small but significant risk of bleeding after this procedure, patients are usually monitored in the hospital for 24 hours after the biopsy.

This biopsy shows a “crescent” in a glomerulus, a feature of glomerulonephritis which can be seen in ANCA-associated vasculitis (GPA or MPA).

3. Sural Nerve Biopsy: The sural nerve is a sensory nerve over the lateral aspect of the foot. Under local anesthesia in an operating room, a surgeon removes a small piece of the nerve, usually along with a piece of the adjacent muscle (the gastrocnemius). Because the sural nerve does not innervate muscles (remember: it is a sensory nerve, not a motor nerve), the patient does not lose any strength on the side of the foot and lower leg. There maybe, however, some residual numbness on the side of the foot. Patients generally tolerate this numbness well (if the vasculitis has involved the nerve severely enough, some patients already have numbness in that region).

Below is the surgical site of a sural nerve and gastrocnemius muscle biopsy one week after the procedure: a few sutures and a thin, well–healing scar.

4. Temporal Artery Biopsy: Performed to diagnose Giant Cell Arteritis, also known as Temporal Arteritis, because the temporal artery is often involved. The temporal artery courses up the temples, just in front of the ears. The biopsy, done under local anesthesia, is performed by making a small incision just above the hairline (sometimes shaving a small area of hair is required). The procedure is extremely well–tolerated by patients. Within several weeks, there is usually little or no sign that a biopsy was done. Complications of temporal artery biopsies are extremely rare. Sometimes, to increase the diagnostic yield, both temporal arteries (i.e., the ones on each side of the head) are biopsied.

5. Lung Biopsy : Often the best way to make a diagnosis of vasculitis that involves the lungs, such as granulomatosis with polyangiitis (GPA). A lung biopsy may be performed in one of two ways: 1) open lung biopsy, a sizable surgical procedure; or 2) thoracoscopic lung biopsy, a less invasive but still significant procedure. Even a thoracoscopic biopsy usually requires at least 48 hours in the hospital and the temporary placement of a chest tube to permit the lung to re–expand.

6. Brain Biopsy: Often necessary to confirm the diagnosis of Central Nervous System (CNS) Vasculitis. This is usually performed on the non–dominant side of the patient’s brain (that is, if the patient is right–handed — and therefore “left–brained” — the biopsy is performed on the right side of the brain). Biopsy of the brain’s covering, the meninges, is usually performed at the same time.

7. Angiogram / angiography: Angiography is helpful in the diagnosis of Polyarteritis Nodosa (PAN). Similar to a heart catheterization, after inserting a catheter into a large artery in the leg and advancing the catheter into the aorta, radiographic dye is injected into blood vessels supplying the gastrointestinal tract. In the proper clinical setting, the detection of aneurysms (small outpouchings of blood vessel walls) is diagnostic of PAN. This gives an accurate picture of the luminal (inside) anatomy of blood vessels.

8. Central nervous system angiogram Frequently part of the “work–up” of CNS vasculitis. The procedure is identical to an abdominal angiogram, except the catheter is advanced all the way up to the large vessels supplying the head and neck (for example, the carotid arteries). On angiography, CNS vasculitis is characterized by “beading” (dilated areas alternating with narrowing of the blood vessels). A strikingly abnormal angiogram may eliminate the need for a brain biopsy.

The angiogram pictured shows prominent dilations of arteries visible at several sites in the intra–cerebral region.

9. Other Useful Tests: There are many other tests that are helpful in the diagnosis of vasculitis, or in evaluating the activity of the disease:

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR): Also known as the “sed rate”, for short. This is an old but useful test first employed by the ancient Greeks as a test for pregnancy. It is important to note that there are several influences on the ESR such as anemia and hypergammaglobulinemia which may have nothing to do with an inflammatory state.

C–reactive protein (CRP): CRP is a protein produced by the liver in response to inflammation within the body.

Urinalysis: Many forms of vasculitis affect the kidneys. A simple way of determining whether or not the kidneys are involved is to perform a urinalysis. By performing checks for several indicators of inflammation in a patient’s urine, the physician may determine if inflammation is present within the kidneys. These indicators include:

- Protein (“proteinuria”)

- Red blood cells (“hematuria”)

- Clumps of red blood cells (“casts”)

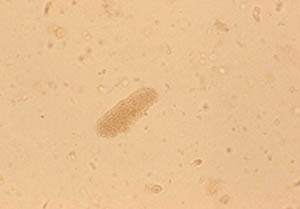

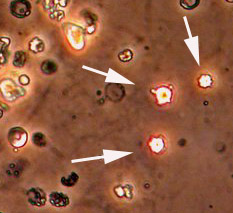

Pictured below is a urine specimen from a patient with Wegener’s granulomatosis and glomerulonephritis (inflammation in the kidneys).

This is a view of the specimen examined under the microscope, showing cylindrical “casts” comprised of red blood cells. This finding strongly indicates vasculitis in the kidney.

From another Wegener’s granulomatosis patient’s urinalysis, “blebs” (identified by white arrows) protrude from the surface of the red blood cells that have been damaged in transit through the kidney.

Because inflamed kidneys leak blood, red blood cells — dismorphic as these are — appear in the urine.

CT Scan (a CAT scan, or computed tomography) — A type of radiology test that permits a non-invasive, cross–sectional view of a patient’s anatomy. On the illustration below (a chest CT scan from a patient with GPA), the view is up (looking toward the patient’s head, from his or her feet). The heart is the white, rounded object in the upper center of the picture. The black regions are the patient’s lungs. The large spot in the left lung (corresponding to the patient’s right lung) is a nodule caused by GPA. Other smaller nodules are also evident.

MRI / MRA: MRI is another imaging modality that can be useful for diagnosing and following systemic vasculitis; particularly large vessel vasculitis. MRI allows for visualization of the vessel wall. In vasculitis, the vessel wall may be thickened or edematous.

ANCA tests — ANCA is an abbreviation (acronym) for anti–neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. These antibodies are found in the blood of patients with several different types of vasculitis, including Wegener’s Granulomatosis, Microscopic Polyangiitis, and the Churg–Strauss Syndrome. ANCAs and their association with vasculitis were recognized in the mid–1980s, and their use has become increasingly widespread since the 1990s. ANCAs are detected by a simple blood test. These antibodies are directed against the cytoplasm (the non–nucleus part) of white blood cells. Their precise role in the disease process remains uncertain but is a topic of considerable research interest. ANCAs come in two primary forms: 1) the C–ANCA [C stands for cytoplasmic] and, 2) the P–ANCA [P stands for perinuclear]. C–ANCAs have a particularly strong connection to Wegener’s Granulomatosis (up to 80% of patients – and possibly more of those with active disease – have these antibodies). When C–ANCAs are present in the blood of a patient with symptoms or signs suggesting Wegener’s, the likelihood of the diagnosis increases considerably. Because of the long list of other conditions that are sometimes associated with ANCAs, however, in most cases it is still VERY IMPORTANT to biopsy an organ involved by vasculitis to verify the diagnosis.

All information contained within the Johns Hopkins Vasculitis Center website is intended for educational purposes only. Visitors are encouraged to consult other sources and confirm the information contained within this site. Consumers should never disregard medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something they may have read on this website.